About

ISAGER

The Danish company Isager has since 1977 been supplying patterns and quality yarns made from natural fibres, both known and loved by knitters the world over. The yarns and patterns are sold in selected shops in Denmark and internationally. The founder of Isager, Marianne Isager, and her daughter and co owner of the company Helga Isager, are behind a line of popular knitting books.

The history of Isager began with designer Åse Lund Jensen (1920-1977), who established her studio in 1960. Åse Lund Jensen’s work was rooted in the Danish crafts tradition, but she took her inspiration in particular from the Icelandic and Faroes knitting cultures. In cooperation with Henrichsen’s Yarn Mill Åse Lund Jensen made a range of high quality woolen yarns and her own favorites Spinni and Jensen Yarn are still part of Isager’s range today.

Åse Lund Jensen was a pioneer in her field and throughout her career she worked continuously to get knitting recognised as a craft, amongst other things through her many exhibitions and her work as a teacher at Skals Håndarbejdsskole, today known as Skals – Højskolen for Design og Håndarbejde (Skals – School of Design and Crafts). It was here that Marianne Isager and Åse Lund Jensen met and founded their friendship. After the death of Åse Lund Jensen this friendship later led to Marianne Isager taking over the rights to use Åse Lund Jensen’s eternally modern patterns and continue the company known today as Isager.

The Isager company now resides on the former Elementary School in Tversted, a village in the north of Jutland close to the North Sea, surrounded by beautiful countryside. Here the company’s retail shop, wholesale and workshop centers are all situated.

By Kirsten Toftegaard, Curator and keeper, Designmuseum Danmark

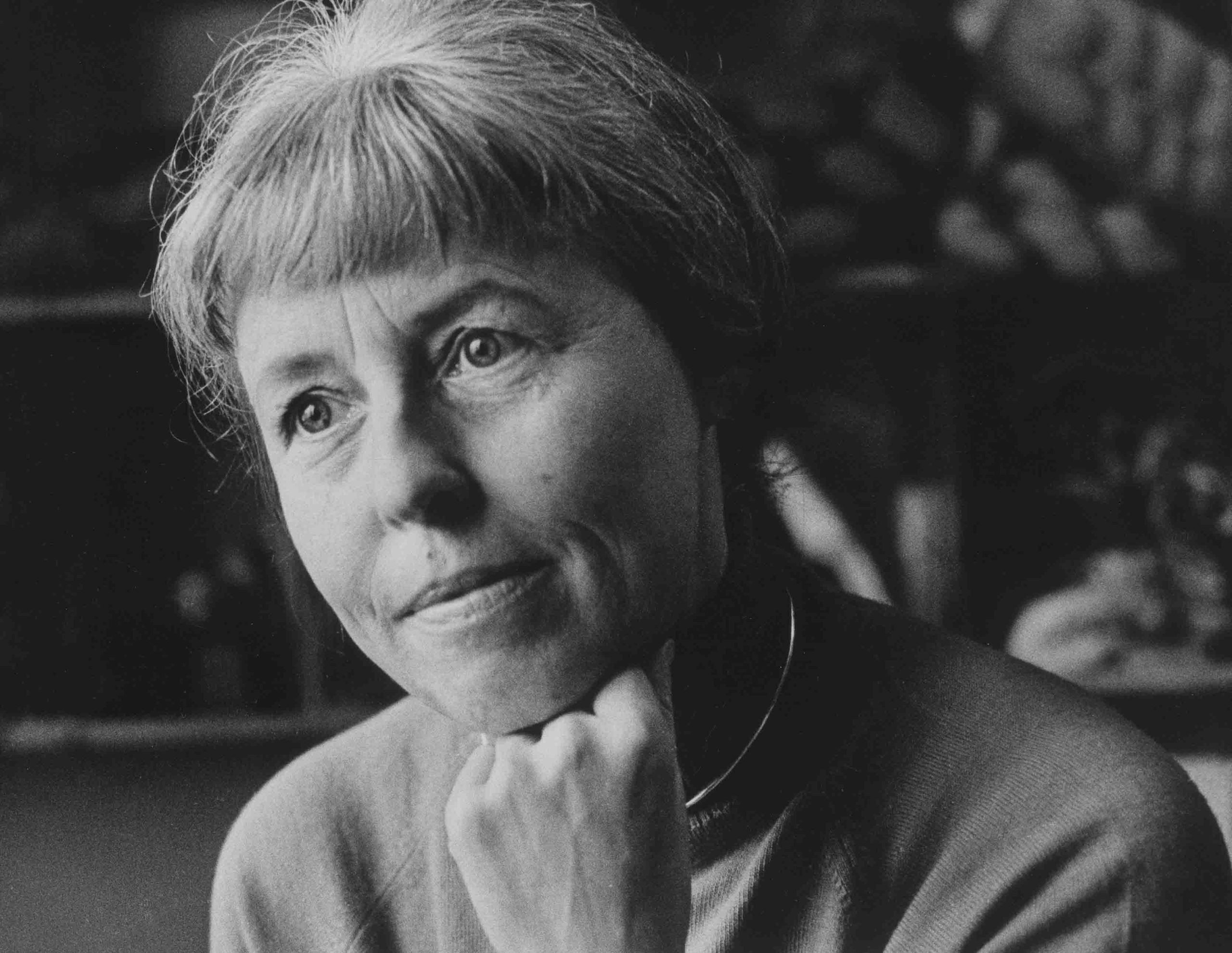

Åse Lund Jensen

Åse Lund Jensen, 1967. Photo: Ebbe Andersen

”Knitting is not only a passion, it takes knowledge.”

”It has to be a hobby, a relaxation to knit” some people say – to me knitting is a science”

ÅSE LUND JENSEN

Both of the statements above clearly demonstrate the seriousness with which the knitting designer and author Åse Lund Jensen (1920-1977) regarded her subject – handknitting. Åse Lund Jensen was one of the 20th century’s pioneers within textile art, along with other prominent female textile designers, such as printer, Marie Gudme Leth (1895-1997) and weaver, Paula Trock (1889-1979). Her pioneering work was centered around handknitting and its introduction as an independent artform within textile art in Denmark. Where design was concerned, Åse Lund Jensen’s inspiration came from the Nordic countries, particularly the Danish knitting tradition with the multitude of beautiful and special patterns that she developed and gave an independent and personal design. Her patterns were created to a highly artistic and technical level, and she developed new and more modern yarns and colours, inspired by plant dyeing, toned down and well suited to the Danish customer. She found they suited the Danish customers better than the existing sharp colours. In 1960 she set up her own workshop where she created collections of hand-knitted garments, sold in shops like e.g. Den Permanente. In those days about 60 knitters worked for her. Eventually the customers wanted to knit the sweaters themselves, and she began an intense educational work, which was something that had not been done before.

Åse Lund Jensen published several books on knitting, and they can still be used today because they are clear and logical in their composition as well as in their aesthetic presentation. Today the books are regarded as classic knitting literature. Thus, Åse Lund Jensen left an essential heritage within Danish textile craft when she died far too early in 1977.

Education and beginning.

As a young woman, Åse Lund Jensen was very interested in fashion and this led to her working as a trainee in haute couture at the tailoring section at the department store Illum’s fashion salon where garments were tailor-made for individual customers, and most of the work was done by hand. The training provided Åse Lund Jensen with an exquisite feeling for the three-dimensional body and this know-how was to be very useful to her in her work with the design of her knitted garments. Later in the 1960s she improved her knowledge during a course at the Tailoring Academy.

In 1951 Åse Lund Jensen graduated from the then School of Arts and Crafts in Copenhagen as a commercial designer. She and her husband then left for Greenland, where they started a family. Here she became interested in the Greenlandic leather and pearl crafts. She began collecting these and tried to transfer their patterns to cross-stitch embroidery, knotting, patchwork, crochet work, braiding and of course knitting. As a result of this interest Åse Lund Jensen published a small bilingual book (Greenlandic and Danish), published in 1958: 38 knitted and embroidered pieces – arnanut agssagsugagssat. The book was sponsored by the Ministry of Greenland. Gertie Wandel (1894 – 1988) long time president of the Danish Handcraft Guild, wrote in the preface that hopefully the book would perform a mission in spreading the patterns and thus renew Greenlandic handcrafts. She finished the preface by expressing her wish:

“that the book would be so widespread that it would really have the impact on the cultural promotion of women’s handcrafts, intended by the Ministry of Greenland.”

The first book on knitting and the workshop for handknitting.

Back in Denmark Åse Lund Jensen published another book in 1959 in co-operation with Karen Lind Petersen, titled Contemporary Knitting inspired by Danish Folklore Patterns; this book was all about the knitting patterns. As the title reveals, the book was based on Danish peasant textiles and knitting traditions. In The National Museum of Denmark and The Danish Museum of Decorative Art (today Designmuseum Danmark) the two authors had studied knitted sweaters and blouses and their patterns up through the ages. These patterns they now adapted to more modern sweaters. The inspiration came e.g. from the plain damask knitted jackets from Lolland and Falster (in Danish nattrøjer) which were part of the women’s clothing. (Damask knitting is inspired by the damask weaving technique. In knitting the effect of the pattern is obtained by knitting purl stitches on a plain background.) But also traditional Danish weaving patterns, like e.g. fustian were introduced and adapted to knitwear. For other sweaters the knitting patterns from the Faeroe Islands were used as basic design. Included in these designs were also the characteristic sweaters with the decorative false seams along the sides, round the armholes or along the sleeves, where the increasing or decreasing provided an excellent fit.

In 1972 Åse Lund Jensen told the professional magazine Dansk Brugskunst about her workshop and stated that with her book from 1959:

“…. my work with knitting had really started. This was towards the end of the 1950s, when the Norwegian sweaters with star patterns and pewter buttons where really in, and where a visit to Norwegian museums quickly revealed that proper Norwegian sweaters really were accused of a lot of nonsense.”

As early as within the first decades of the 20th century, Denmark saw the beginning of several individual workshops, all of them working with either embroidery, weaving or textile printing, but no knitting workshops, because knitting was not then regarded as an independent craft within arts and crafts. To Åse Lund Jensen knitting was no hobby – it was an independent field and therefore in 1960 she established her own workshop for hand knitting, where it was her ambition to create collections and develop new patterns to a high technical and artistic level.

”My aim is to obtain a fit for knitwear equal to that of tailor made clothes.”

Åse Lund Jensen on knitting a fitted garment, 1972

The Patterns

Åse Lund Jensen missed new, original knitwear, produced in Denmark, and she wondered why the Danes copied, almost to the exclusion of everything else, Norwegian sweaters or other patterns from abroad, despite the fact that as well as other Nordic and Baltic countries, Denmark had a rich knitting tradition. People who wanted to knit were left to use commercial patterns in the form of – according to Åse Lund Jensen – cheap, glossy prints sold with the yarn, or they had to use the patterns in the weekly magazines.

Where shaping her garments were concerned, Åse Lund Jensen wanted to abandon the schematic shape consisting of one tube for the body and two smaller tubes for the sleeves. Inspired by her training as a tailor and by her knowledge of the three-dimensional body, it was her wish to add shape and a proper fit to each pattern. For every pattern as well as for every size of the pattern, she cut a paper pattern and calculated the number of stitches, the size of knitting needles and a possible basic knitting pattern. In 1972 she stated that:

“My aim is to obtain a fit for knitwear equal to that of tailor made clothes. In other words I try to create the same fit that can otherwise only be achieved through using a sewing pattern. The only complication being that now the fabric, the shape and the knitted pattern has to be created in one operation.”

To avoid bulky seams, frequently giving the garments a sad “homemade” look, the garments were knitted in the round, which could then be continued on the yoke with raglan sleeves.

Åse Lund Jensen started designing patterns with small repeats, inspired by Faroese jacquard knitting patterns i.e. multicoloured knitwear consisting of harmonious patterns with minor floats on the work’s wrong side. The patterns covered the entire surface, thus giving it a textural and structural character, as opposed to the Norwegian patterns where the surface was broken up into several and more unconnected patterns – at least according to Åse Lund Jensen. The patterns had to be executed to perfection to fit the shaping of the jacket, so that they were laterally reversed, whenever the number of stitches had to be altered because of the shape, and so that the necessary decreasing and increasing were turned into an ornaments in themselves. When working with a pattern in varying sizes, it might be like a jigsaw puzzle to fit it all in.

Yarns and Colours.

In 1970 Åse Lund Jensen applied for a membership of Den Permanente (a Danish crafts cooperative), because she felt that this was the right place for her to show the results of all her knitting experiments. Den Permanente, established in 1931, was a private association and a collective sales organization, which accepted artists and craftsmen. The purpose of Den Permanente was to show arts and crafts from smaller workshops which had no showrooms or sales facilities. All the displayed objects had to pass through a board of censors, selected among the members, and the censors were instrumental in maintaining a high standard. Åse Lund Jensen was turned down because the colours in her yarns were not satisfactory.

Unlike weaving yarns, which were found in beautiful, matching colours, the knitting yarns in those days were mainly found in very crude colours. Åse Lund Jensen stated that:

“some rather odd ideas exist about the colours of knitting yarn. They have to be bright and consequently one imagines red or blue, and the companies see these as glaring colours. It seems that bright colours are always glaring. I also use red and blue, but I have just taken “the bite” out of them. There are also strange traditions concerning male or female colours. There are certain brown colours, light as well as dark, right now a beige colour that are wearable for males, but the latter is not to be found in the colour charts available. I am in no way opposed to strong colours. I want a flaming pink in my patterns, but it is to be just as carefully toned as the other colours in my colour scheme, which it has taken me years to obtain. Strange that nothing has been done to modernise the colours in knitting yarns”

Åse Lund Jensen started working with Henrichsen’s Wool Mill in Skive in Jutland. They were experts in dyeing the yarns and they were also part of developing the special yarn qualities. By developing these new qualities, she followed in the footsteps of her rolemodel, Paula Trock.

Because of the huge lack of materials for hand weaving during World War II, Paula Trock became aware of the fundamental importance of the quality of the materials for a good end result. Before the war all weaving yarns were imported because the Danish wool had not yet reached a level of quality making it useable for weaving high end goods. In 1948 Paula Trock started “Spindegaarden” in Askov in Jutland, and here she experimented with the early treatment of the wool both scientifically and practically. On her imported British manual spinning machines she wanted to develop and spin new lighter yarns, better suited for hand weaving than the industrially spun yarns. Her new types of yarn gave rise to a lot of interest, not only in Denmark but also abroad, and Paula Trock was duly recognized for her production of the new lighter yarns, which were equally well suited for garments and for decoration. In cooperation with Henrichsen’s Wool Mill Åse Lund Jensen developed the single ply Spinni, the three-ply ÅLJ and the four-ply and thicker Hebridia natural wool.

When Åse Lund Jensen created her own colour scheme, her initial choice was the production of 12 cool shades of grey, green, earthen brown and indigo blue colours, all of them matching each other. The colours were classic, inspired by plant dyes. It was her conscious choice to leave out the changing colours in fashion. In 1972 the colour chart included 30 colours. Later Marianne Isager was able to double the number of colours by using the same dyes on a melange yarn, made from black and white lamb’s wool (the ‘s-colours’). Added to those were an unbleached off-white and a black yarn.

By now Åse Lund Jensen had been admitted as a member of Den Permanente. In her work with the dyeing she was probably inspired by the dyer from Vejle, Ejnar Hansen (1885-1958) who was an ideal to Åse Lund Jensen. Ejnar Hansen became known for his huge and almost scientific work with natural as well as chemical dyes and their aesthetic and practical values. He worked with a number of weavers and architects to recreate and obtain the same harmonic effect in chemical dyes as was often seen in natural dyes. He was known and respected by professionals and colleagues within arts and crafts, and Åse Lund Jensen has probably seen the commemorative exhibition arranged by The Danish Museum of Decorative Arts in 1961.

”It seems that bright colours are always glaring. I also use red and blue, but I have just taken “the bite” out of them.”

Åse Lund Jensen on colours in knitting, 1970

Cooperation and Sales.

Although Åse Lund Jensen initially also sold her finished garments, she created patterns for various companies and institutions, so that the customers could knit their own personal garments. During the two years, 1968 – 1970, where she worked with Illum’s yarn department, Åse Lund Jensen designed garments such as jackets, sweaters, skirts, dresses and pixie caps, but she also undertook the design of more unusual things like slacks, jumpsuits, ponchos and bags. For some of the sweaters and jackets Kirsten Uldbjerg wove beautifully matching material, thus enabling the customer to knit and create a matching outfit. In 1969 Åse Lund Jensen designed patterns for eight different children’s dresses, in six sizes covering two years to twelve years old for Illum’s yarn department. A lot of work and thorough preparation went into the making of a pattern. Firstly each size was sewn in cotton and then test knitted several times. The entire preparation took up most of a year, but then the collection was a huge success.

For the Icelandic Handcraft Guild (Heimilisiðnaðarfélag Islands) Åse Lund Jensen designed model knitwear in unspun yarn (lopi), and she designed knitted pieces with accompanying patterns for Højskolernes Håndarbejde (Folk High School Craft), situated at Tyrebakken in Kerteminde on Funen, which also housed the School of Handcrafts and where she was a teacher from 1971 to 1973.

From the 1950s many Danish textile printers and weavers were very active within the design and production of clothing in a bohemian/artisan style. These clothes were often unique, or were produced in a limited number. In some cases, it was also a question of demands and second editions were made. This type of clothing were sold through special shops, like e.g. Den Permanente where from the mid1950s, clothes designed by various artists were for sale in the shop. At the same time Den Permanente was responsible for some of the most frequented exhibitions of bohemian clothing, and they also arranged fashion shows with these clothes. Among artists, architects and other design conscious people this style of dressing was very popular and even Illum’s Bolighus arranged shows with their own collection under the heading “garments matching their environment”. In cooperation with weavers Lisbeth Have (1930-1997) and Annette Juel (b. 1934) and textile printers Susan Holm (b. 1937) and Tusta Wefring (1925-2014), Åse Lund Jensen set up the shop Opus (1976) in Store Kongensgade in central Copenhagen, and from here they all sold their clothes.

The Educational Aspect: the books

Because she regarded handknitting as a profession and not only as a hobby, Åse Lund Jensen also found that handknitting demanded the same kind of training and education as other branches of textile arts and crafts. During the first period after setting up the workshop in 1960, she sold a number of readymade knitwear, just like other textile artists, such as weavers or printers sold their readymade works. With the increasing demand for patterns and yarn, enableing the customers to knit their own models, Åse Lund Jensen took on a completely different aspect of her profession, namely the educational aspect. So apart from delivering thoroughly designed models, which were technically well-prepared and artistic, she now wrote thorough and well written patterns and educationally clear books on knitting.

She states:

”When I deliver a pattern and yarn for a sweater, all I ask is for the customer to follow the manual and the knitting tension. I calculated the pattern and the size, all she has to do is follow the knitting pattern and tend to the tension of the knitting….”

Only few of the patterns had photos; characteristic of her patterns were the handdrawn illustrations, adding something artistic to them. In 1974 she published the book: Knitting – knitting techniques and the calculation of patterns. Here she dealt with basic skills within knitting, like casting on and off, increasing and decreasing, vertical and horizontal shaping as well as knitting things together or making seams. An essential section describes how to calculate a pattern, so that the knitter was able to alter the knitted garments and patterns according to test samples, so that the finished product would fit the individual body perfectly. Besides, the book contains a small number of Åse Lund Jensen’s models. In 1976 another book was published, titled Knit something else – curtains, wall-hangings, room dividers or rugs, thus extending the idea of what might be knitted. The alternative knitting patterns in the book resembled some of the experiments otherwise characteristic of the textile art in the 1970s.

When the younger generation rose against the authorities towards the end of the 1960s, another movement also gathered momentum, namely women’s rights to their own bodies as well as equal rights in all areas of society. Even the female textile artists rebelled – just like today more women than men worked with textiles as a media within art. In a major exhibiton in 1968 at the Danish Design Museum a group of Danish and Swedish textile artists set things in motion, and the pictorial weavings began to be liberated from the walls and from the square frames. Every kind of material in various constellations were possible, new stuctures and shapes arose and the textile art took possession of the room with sculptures created in free textile techniques.These experiments within free textile art continued thoughout the 1970s, and when Åse Lund Jensen published a book with patterns showing how to knit room dividers and lampshades – it was actually part of contemporary trends.

Acknowledgements – Exhibitions and Prizes.

In 1971 Åse Lund Jensen exhibited at the Nordic House, Reykjavik, apparently the same exhibition which was shown in 1972 at Den Permanente where members also had various, minor exhibitions. In 1974 she was invited to exhibit handknitted garments at The Danish Museum of Decorative Art. The title of the exhibition was “Knitwear in Wool”, and she felt it was a great acknowledgement of her work with handknitting. The exhibition was later set up at Herning Museum.

In 1981, a few years after her death, the The Danish Museum of Decorative Arts showed about thirty of her shawls. These shawls were from an unfinished manuscript for a new book which Åse Lund Jensen had been working on. While living in Greenland she frequently visited Iceland. Here the old knitted shawls fascinated her, and she measured and reconstructed them. She had also worked with reconstructions of old shawls from the Herning and Himmerland area, as well as from the Faeroe Islands, just as the so-called Roman shawls were adapted to new yarns and perhaps other knitting techniques. All the shawls had been designed and initiated by Åse Lund Jensen, but Marianne Isager (b. 1954) finished them. In 1977 Marianne Isager took over Åse Lund Jensen’s workshop, including the rights to the yarns, the colours and all of Åse Lund Jensen’s patterns. These patterns and the yarns could be bought after the exhibition at Den Permanente, as well as at the shop Hanne Hansen, Fiolstræde in central Copenhagen.

In 1975 Åse Lund Jensen received another distinguished acknowledgement, namely the arts and craft prize. She was awarded this for her pioneer work in several areas: developing her own yarns and a more harmonious colour chart, undertaking further education through the publishing of knitting books and through the spreading of quality knitting to a wider group of people. This was done through the instruction of how to calculate the correct fit of a model, but also through an inspiration to knit something else apart from garments, such as room dividers etc.

Throughout her life Åse Lund Jensen remained a hand knitter, with an emphasis on “hand”. In an interview she expressed her sharp attitude to machine knitting, saying:

„Oh yes, one can even knit patterns on those apparatuses, and it looks really nice – just like false teeth.”

Åse Lund Jensen on machine knitting, 1970

By Tove Engelhardt Mathiassen, Director of Den Gamle By (The Old Town museum)

Political knittwear a danish phenomenon

The 1970s phenomenon, hønsestrik, ”political knitwear” originates directly from a feminist group in Espergærde, where as in so many other locations in Denmark, women met to discuss politics, the oppression and liberation of women. As regards time, the essential period for political knitwear stretches from 1973 until 1980; the phenomenon, however, has left its permanent mark on the Danish language as the word ”hønsestrik” has found its way into our dictionaries. It is impossible to translate, so when I was curating the exhibition ”Hønsestrik and Hot Pants” in the museum Den Gamle By in 2014, I translated it into ”political knitwear” in the English texts.

The personal is political

Looking at the knitting and the phenomenon, one also has to consider the political climate in the beginning of the 1970s. In those days female political positions and feminism were growing rapidly, so political knitwear was part of a comprehensive political movement. In 1970, the Danish feminist movement was established under the slogan: ”No women’s lib without class struggle, and no class struggle without women’s lib ”, along with the equally important ”The personal is political”. Both these slogans meant something to the women who invented political knitwear. It was a part of the political struggle aiming at liberation and freedom. In 1971 the Danish feminist movement initiated the first women’s summer camp on the small island Femø, and after the camp a group of women occupied a condemned building in the street, Aabenraa, in Copenhagen and set up the first feminist community centre in Denmark which consequently became the home base for political knitters.

The beginning

Kirsten Alma Hofstätter (1941 – 2007) was a keen collector of press cuttings, and in her scrapbooks one can follow the beginning of what would grow into a knitting trend and into a left-wing women’s publishing company, called “Hønsetryk”. As early as the summer of 1972 Kirsten Hofstätter published knitting patterns in a weekly magazine, Søndags B.T. In here, she explains how people stop her in the streets to inquire about the patterns in her family’s jackets and sweaters. The pictures reveal the entire family in colourful, home-knit garments with borders of little figures like butterflies, masks, horses and men in top hats. The patterns were depicted on squared paper, so that the readers of the magazine might copy them; but there are no technical explanations nor any patterns for how to knit the various garments shown in the pictures. This lack was also criticized by a reader in a later issue of the magazine under the headline: Disappointing knitwear.

The books and the publishers

The first knitting book on political knitwear, Hønsestrik, was published in December 1973 with a number of 4000 printed copies. It was a question of rebellion – and then the idea of Hønsestrik (political knitwear) expressed left-wing politics and women’s liberation. The patterns on the squared paper now also included political messages in the shape of feminist symbol both with and without the fist in the centre. This could not be found in the magazine. In fact, the title of the first book on political knitwear started out as The Knitting Manifesto. Kirsten Hofstätter, Loa Kampbjørn and Birte Troest issued the book at their own, newly started publishing company “Hønsetryk”, named thus because none of the established publishers, not even the left-wing “Røde Hane” would take on publishing the book. As late as February 2016 the newspaper “Information” discussed the birth of the publishing company “Hønsetryk”. The left-wing politician, Preben Wilhjelm, who was the co-founder of “Røde Hane”, declares that they could not undertake the publishing of the knitting book for financial reasons, and because the manifesto did not fit their publishing profile. Besides, he writes that personally he suggested to Kirsten Hofstätter that she started her own publishing company.

In an interview from February 1975 Kirsten Hofstätter declares that she had addressed three publishers, but that none of them would publish the book the way she wanted it done. She does not give the names of the companies, but tells, “the third publisher found it screamingly funny that they should waste their time on something so worthless”. Therefore, the women set up their own company and in the first book on political knitting, it was stated directly that the book should be seen as a challenge to the yarn companies, which only handed out patterns, provided one bought their brands. They wanted to settle with books naming a special brand of yarn for each pattern, and last, but not least, it was “a rebellion against fixed patterns that do not allow the knitting people to use their imagination and express their dreams in the knitwear.”

„In January 2017, a new strong movement using knitwear as a political symbol cropped up. The pussy hat project aims at fighting for women’s rights; the supporters knit and wear pink hats as very visible symbols for women’s equality and anti-president Trump-signs.”

Tove Engelhardt Mathiassen

Åse Lund Jensen and political knitwear

Towards the end of the first book, there is a section on knitting samples and stitch numbers, so that the readers may work out their own patterns. In her letter about meeting the knitting women in 1974, Åse Lund Jensen says that they regarded tension in their knitwear as irrelevant. However, this is not quite true, if one reads the book, which had already been published at that time. It is true though, that there are more technical explanations in Hønsestrik 2. The first book sold tremendously, so in the first months of 1974 two new editions were published, so by the end of April 1974 the book had been published in no less than 30.000 copies. The book was sold in the feminist community centre in Copenhagen, through Co-ops and in book cafés all over the country. In 1974, Hønsestrik 2 was published and here Åse Lund Jensen had a 4-page article on knitting from a historical point of view. She also tells how to knit with yarns in two colours in stockingstitch as well as purl stitches without having long loose strands on the back. In the first book, they recommended knitting on circular needles in order to avoid purl stitches. The book had several political symbols on squared paper, the anti-atomic symbol, hammer and sickle and as something new male and female symbols and the last with the fist in the circle. Åse Lund Jensen writes in her letter that she had to help them with the symbols, so that the circle became circular. At my meeting in 2015 with Gunnar Stein, who worked for “Hønsetryk”, he told me that he had made the working drawing. Thus, there is a little uncertainty as to Åse Lund Jensen’s role in connection with the political knitting.

Final remarks

We will just go back to the opening on political knitting, which cannot be directly translated into English. When Kirsten Hofstätter published the book “Everybody’s Knitting” in 1978 on Penguin, the text was devoid of the political contents found in her first two books. So she never tried to pass on that part of the idea to the English readers. The publishers “Hønsetryk” closed in 1985 after 69 books, dealing with knitting and various other topics. “Hønsestrik” is back in fashion but without the political aspects evident in the 1970s. And yet. In January 2017, a new strong movement using knitwear as a political symbol cropped up. The pussy hat project aims at fighting for women’s rights; the supporters knit and wear pink hats as very visible symbols for women’s equality and anti-president Trump-signs.

Åse Lund Jensen’s letter to Marianne Isager after Åse’s meeting with “The Hen Knitters”, 1974

Dear Marianne Those hen knitters! Yes, I had spent quite a lot of time pondering and I almost came to care for them, as it does not happen every day that someone makes a knitting book of their own accord. The long and the short of it is that I invited them over to have a talk about knitting, knowing full well that to them I must represent someone bourgeois, prissy and everything else worth protesting against. They came into my house dressed in these curious garments with knitted feminist and anti nuclear symbols, which we see in their book. They do not, however, frighten me with this and the girls were actually really nice and definitely not unintelligent, even though they think different from me. And it is always good to meet people who ardently commit themselves to a cause, is it not? We had a very constructive meeting this morning. Of course they blamed me for making perfectionistic knitting patterns, forcing people into a set mould, as they should be able to create freely. I too think that this must be the ideal, so this we could not disagree upon. Where patterns are concerned I still think that either you allow people to use the yarn as they like – which I do – or you make an instructive pattern, so as to give the knitter the best possible chances to safely achieve a perfect result – protesting against the yarn mills and patterns in women’s magazines, which they rage against. And yes, they had to admit that this too was consumer friendly. Nevertheless the girls think that knitting should be intuitive. I told them about my book, where we show no other garments than those we use as samples, but on the contrary write page up and page down about how this and that is executed as well as how it looks. Specifically in the hope that this will enable people to throw all patterns – my own included – overboard, and create their own. This they understood. But all this futile talk of tensions, then? Fortunately I had a poncho with big round-shaped patterns by me, and they were curious to know how I managed to get the precise, round shape, as they had severe difficulties with their feminist symbol. Yes, this is all down to precisely that boring tension. Then I showed them the entire process behind creating a circular shape, and this got them very interested. Would I be willing to illustrate this in their next book? But I could not keep myself from teasing them a little and said, that surely it was best if we let people be creative and not to enforce anything on anybody, would it not? So did they not think it a better idea, if we were to teach the knitter how to make any circle in any type of yarn – or a cross for that matter, for those with Evangelical tendencies. They became slightly upset, but in April I will begin as an employee working on the next hen book, so that you know. Even old knitters can learn new tricks, and we parted in high spirits. Well, I had better get on with my day and all the best to you.

Kind regards Åse Holte

1st March 1974

-

Spot Cloth

Marianne Isager & Åse Lund Jensen

From: kr. 474,00 -

Arrows

Åse Lund Jensen

From: kr. 257,00 -

Chains

Helga Isager

From: kr. 947,00 -

Åse’s Stripes

Annette Danielsen

From: kr. 536,00 -

Goose Eye

Åse Lund Jensen & Marianne Isager

From: kr. 673,00 -

Hen-Knit Sweater

Marianne Isager & Åse Lund Jensen

From: kr. 486,00